Students attend Dayton Literary Peace Prize Author Series

Students engage with Yaa Gyasi’s “Homegoing” in and outside the classroom

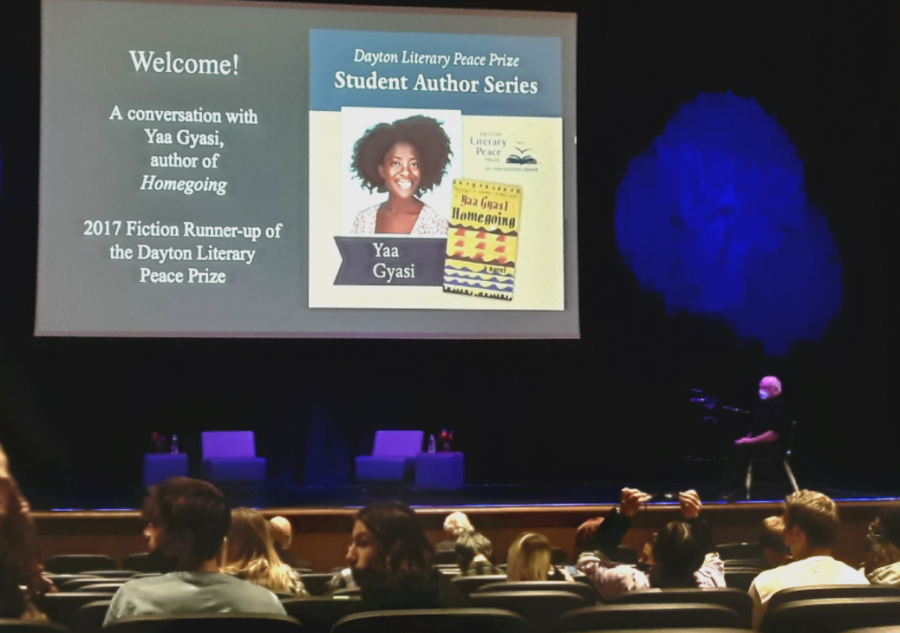

Real-world Relevance: Students from all around the Dayton district settle into Fairmont High School’s auditorium to hear Yaa Gyasi’s insight on her novel “Homegoing,” a book about the Fante and Ashanti tribal regions. Gyasi said, “I wanted to focus on those two ethnic groups as a way of thinking through my own lineage.”

In a world of conflict, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize works to overshadow strife with peace and has done so since it was founded in 2006. This international award has acknowledged authors of fiction and nonfiction whose books offer readers a window into another perspective. In 2017, they awarded author Yaa Gyasi for her novel “Homegoing” and invited her to speak on her novel this year. Now, Gifted Education teacher Katie Poppa and English teacher Emily Sullivan sponsored a book study and access to a presentation with the author.

“Her being such a talented researcher was really intriguing,” Sullivan said. “It spoke to why I was naturally engaged with the historical parts because it was so accurate and I appreciated that.”

Gyasi herself mentions how much research the novel required during her presentation, as “Homegoing” tracks generational racism within the Ghanian Fante and Ashanti tribes. She tells students about how her novel took seven years to complete.

“Her thought process of taking it bit by bit was very down to earth,” Elena Zois (9) said. “She made such a masterpiece.”

Because Gyasi spent years on her debut novel, her plans for the story developed over time, and she explains exactly how this altered the path of the book.

“I started out thinking that the book would be much more traditionally structured, like it was set in the present and then flashbacked to 18th century Ghana,” Gyasi said. “As I was writing, I realized I was more interested in being able to see the way slavery and colonialism shifted these countries and these people in stark ways over a long period of time.”

Gyasi achieved her goal, so much so that “Homegoing” offers a family tree to aid readers in keeping character relations accurate whilst reading, for there are many time skips and new characters. But with so many timelines and characters being wrapped into one book, Gyasi had to determine whose stories she would tell, and whose she would not.

“I knew I wanted to end the book in the present and I knew I wanted to start in the 18th century,” Gyasi said. “There were some obvious omissions, like I didn’t write about the Civil War, mostly because I think there are a lot of really wonderful war stories out there. Sometimes I knew the situation, like I knew I wanted to write about the Fugitive Slave Act, and sometimes I didn’t know what the situation was.”

While historical themes are very prevalent within “Homegoing,” Gyasi touches on the ways in which her personal life filtered through her writing in addition to that.

“I mostly came up with each individual story,” Gyasi said. “The way that ‘Homegoing’ was most influenced by my personal life is the fact that I’m Ghanian; my mom is Fante and my father Ashanti so I knew I wanted to focus on those two ethinic groups as a way of thinking through my own lineage. But aside from that, none of those characters are based on any genealogical research that I did into my own life. But sometimes a real historical figure would lend me an opportunity to think about who a character is.”

One instance of this can be found within one of Gyasi’s characters, Quey, who is loosely based on Philip Quaque, an African minister during the 18th century. But Gyasi says her character Quey uncovered a new problem when it came to her research.

“I had been working with a book called ‘The Door of No Return’ by William St. Clair, a really great book that took all this archival data about life in the Cape Coast Castle,” Gyasi said. “He mentions that the children of the Unions between the British soldiers and the local women were sometimes sent to England for school and came back to form Ghana’s upper and middle classes. I wanted to set that [Quey’s] chapter in England but I really could not find anything about these kids and what their days looked like.”

Despite this, Gyasi didn’t give up—she mentions how she drafted that chapter numerous times before getting right, and that notion stuck with part of her audience.

“I loved how she talked about false starts,” Sullivan said. “I appreciated how she said that so seamlessly because false starts are a part of life.”

Grace Stafford finds relevance not necessarily within Gyasi’s presentation, but directly within her book.

“It [‘Homegoing’] shows the evolution of racism and how far it goes back,” Stafford (10) said. “And especially how it still shows up in our society today.”

Gyasi’s presentation gives insight into a novel that deals with significant societal issues. It is a commentary on racism through a fictional lens, and the many takeaways that students discover are testaments to the intrigue that “Homegoing” holds, leading to more awareness of prejudice and knowledge of past historical events that continue to have an impact.